Strabismus

Overview Symptoms Causes Treatment Convergence insufficiency Amblyopia

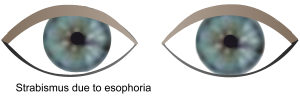

Strabismus is commonly identified as being crossed-eyed, wall-eyed, or having a wandering eye. One or both of the eyes may turn out (esophoria), in (exophoria), up (hypophoria), or down (hyperphoria), or in rare cases, one eye may rotate (cyclophoria). Damage to the third, fourth, or sixth cranial nerve, due to nerve pressure, head injuries, or poor blood supply can cause strabismus.

Types of Strabismus

Strabismus can be categorized in a number of ways:

Strabismus can be categorized in a number of ways:

Direction of misalignment. This is the most common categorization, involving: exophoria (outward divergence), esophoria (inward convergence), hypophoria (one eye deviates downward), hyperphoria (one eye deviates upward), and cyclophoria (the vertical axis of one eye rotates right or left compared to the other).

Duration. Strabismus can manifest in a continual or intermittent manner, sometimes it occurs during stressful situations. Doctors recommend that continual/constant strabismus be treated immediately and aggressively.

Paralytic or non-paralytic. Damage to one of three of the twelve cranial nerves versus a structural problem is another way of describing the condition.

Comitant versus noncomitant. In patients with comitant strabismus the eye misalignment exists regardless of the direction of their gaze. In noncomitant strabismus, the deviation shifts or increases, depending on the direction of gaze.

Signs and Symptoms

Esotropia

- Suppression. The brain blocks all or part of an image.

- Eyestrain.

- Depth perception problems.

- Slight head tilt to right or left, or chin rotated up or downward. Some of these tilts are symptoms of nystagmus, in which the eyes make repeating and uncontrolled movements.

Exotropia

- Double vision.

- Suppression.

- Adaptions. People with intermittent exotropia often develop adaptations that allow them to suppress or ignore the image from the wandering eye and therefore they will not notice the double vision. During the time the eyes are straight, the suppression is absent and both eyes see normally as a team. If the eye-turn is constant, a lazy eye may develop.

- Light sensitivity. This is also a common complaint.

Strabismus Causes

Genetic. Researchers have learned that patients’ muscles are lacking in certain proteins. Genetic expression of collagens and the enzymes that regulate collagen formation are not sufficiently supported, and genetic expression of collagen-inhibiting enzymes is supported genetically in excess.1 They have also identified genes with alterations that are implicated.2

Nerve disturbances. Strabismus is most often caused by weakness or dysfunction of one or more of the three cranial nerves that regulate eye movement. The cause of infantile strabismus usually comes from the cerebral cortex.3 Disturbances in the neural-control centers may occur with high fevers and childhood illnesses or for other reasons. This may be why studies show a link between the strabismus onset and delay in a child's learning to sit, walk, talk, and control elimination.

Skill delays. Seemingly, the mind pays more attention to the workings of the visual system between four months and six years (especially until three and a half years). Later, the mind is more involved in other learning skills. Delayed neural growth or nerve protective covering, may put binocular skills out of sync with attention necessary to convert eye coordination skills into conditioned habit patterns. Visual habits are more vulnerable if not firmly fixed. Neurological problems such as cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, hydrocephalus, or brain tumors can cause strabismus.4

Trauma. Damage to the visual cortex of the brain, which impacts eye muscle control, can cause strabismus.

Vascular. In adults, strokes or vascular problems can cause strabismus through inadequate blood supply.5 Microvascular disease is the most common cause of cranial nerve palsy.6

Thyroid. In adults, Graves disease and other thyroid disorders can impact eye muscle behavior.7

Premature birth. This and low birth weight are linked to the incidence of strabismus.8

Myopia. Strabismus has been noted in young adults with myopia, and it may be related to close work for long periods.9

Orbital. If there are abnormalities in orbital (eye socket) bones, or masses such as tumors within the orbit, strabismus may indirectly result.10 In addition, orbital connective tissue links to the muscles that move the eye. Abnormalities in these tissues can cause strabismus in the absence of a neurologic problem. 11

Eye surgery. Vitreoretinal surgery is a significant cause of strabismus.12 Refractive surgery is generally effective for exotropia that is related to refractive error. However, patients without apparent strabismus can develop strabismus and/or double vision after surgery.13 Similarly, surgery to implant an intraocular lens can result in strabismus.14

Ocular and related pathologies.

- Duane syndrome is a rare cause of strabismus.

- Sagging eye syndrome, a connective tissue condition, can cause vertical or horizontal strabismus.

- Loeys-Dietz syndrome (genetic) puts children at risk for strabismus.

Conventional Treatment

For esotropia or exotropia, depending on the type and severity, treatment may include surgery, glasses, and/or visual training. Surgery doesn't change the vision, but aligns the eyes by changing the length or position of one or more eye muscles outside the eye. Sometimes botox is used in the stronger muscle and is repeated 3–4 months later. In children, esotropia strabismus is most commonly treated with glasses, but exotropia may require surgical correction. Surgery techniques, such as adjustable sutures, are evolving.

Complementary Approach

Supporting overall vision health through diet, nutrition, exercise, lifestyle, etc. are the basic foundation for the complementary approach to strabismus.

- Key self help tips Maintain good vision with eye disease prevention pointers

- If you are a computer user, please review our section on Computer Fatigue Syndrome

Footnotes

1. Agarwal, A.B., Feng, C.Y., Altick, A.L., Quilici, D.R., Wen, D., et al. (2016). Altered Protein Composition and Gene Expression in Strabismic Human Extraocular Muscles and Tendons. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, Oct 1;57(13):5576-5585.

2. Kruger, J.M., Mansouri, B., Cestari, D.M. (2013). An update on the genetics of comitant strabismus. Semin Ophthalmol, Sep-Nov;28(5-6):438-41.

3. Tychsen, L. (2012). The cause of infantile strabismus lies upstairs in the cerebral cortex, not downstairs in the brainstem. Arch Ophthalmol, Aug;130(8):1060-1.

4. American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. Strabismus. Retrieved May 11 2018 from https://www.aapos.org/terms/conditions/100.

5. Ibid. American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. Strabismus.

6. Gunton, K.B., Wasserman, B.N., DeBeneditis, C. (2015). Strabismus. Prim Care, Sep;42(3):393-407.

7. Ibid. American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. Strabismus.

8. Gulati, S., Andrews, C.A., Apkarian, A.O., Musch, D.C., Lee, P.P., et al. (2014). Effect of gestational age and birth weight on the risk of strabismus among premature infants. JAMA Pediatr, Sep;168(9):850-6.

9. Zheng, K., Han, T., Han, Y., Qu, X. (2018). Acquired distance esotropia associated with myopia in the young adult. BMC Ophthalmol, Feb 20;18(1):51.

10. Lueder, G.T. (2015). Orbital Causes of Incomitant Strabismus. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol, Jul-Sep;22(3):286-91.

11. Peragallo, J.H., Pinesles, S.L., Demer, J.L. (2015). Recent advanced clarifying the etiologies of strabismus. J Neurophthalmol, Jun;36(2):185-93.

12. Chaudhry, N.L., Durnian, J.M. (2012). Post-vitreoretinal surgery strabismus-a review. Strabismus, Mar;20(1):26-30.

13. Minnal, V.R., Rosenberg, J.B. (2011). Refractive surgery: a treatment for and a cause of strabismus. Curr Opin Ophthalmol, Jul;22(4):222-6.

14. Park, K.S., Yim, J.H. (2014). Strabismus following implantable anterior intraocular lens surgery. Int Ophthalmol, Feb;34(1):117-20.

info@naturaleyecare.com

info@naturaleyecare.com

Home

Home

Vision

Vision Vision

Vision

Health

Health Health

Health Research/Services

Research/Services Pets

Pets About/Contact

About/Contact