Vitreous Detachment

What it is Types Symptoms Causes Treatment

Posterior Vitreous Detachment (PVD) affects 75% of people over the age of 65 but may be helped with dietary and nutritional changes. The jelly-like vitreous gel (vitreous humour) is 99% water and takes up the space between the retina and the lens of the eye. As we get older, the vitreous becomes more liquid and causes a strain on the connective tissue and fibers, often resulting in a tear or detachment from the retina.

Next: Nutritional support, diet, & lifestyle tips to support the vitreous.

Next: Nutritional support, diet, & lifestyle tips to support the vitreous.

A vitreous detachment is not sight threatening and requires no medical treatment, however ...

In patients with symptoms of a PVD, there is an incidence of retinal tears of 14.5% and hemorrhages of 22.7%. One study shows floaters in 42%, flashes in 18%, and both floaters and flashes in 20% of patients with PVD and secondary retinal pathology.

Only about 10% of patients with PVD develop a retinal tear; around 40% of patients with an acute retinal tear, if left untreated, will develop a retinal detachment. So, it is crucial to get an immediate evaluation at any first signs of symptoms.

In some cases with a partial vitreous tear, the remaining fibers can continue to pull on the retina, resulting in a macula hole, or potentially, a tear in the retina or retinal blood vessel. Again, this needs to be monitored by your eye doctor.

What is the Vitreous?

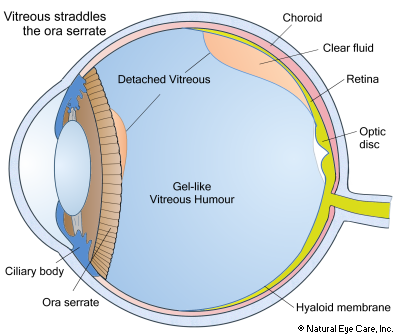

The jelly-like vitreous gel (vitreous humor) is 99% water and takes up the space between the retina and the inner lens of the eye. As we get older, the vitreous becomes more liquid, and it causes a strain on the connective tissue and fibers between the vitreous humor and the retina, often resulting in a tear or detachment from the retina. The vitreous is composed of collagen fibers (about 0.5%), hyaluronic acid (about 0.5%), a small amount of ascorbic acid, and water (about 99%).

Structure

The vitreous humor fills the center of the eyeball, filling the space through which light passes between the lens of the eye and the retina at the back of the eye. Millions of fine fibers contained in the vitreous attach to the retina surface. There are no blood vessels in the vitreous. If a substance enters the vitreous humor, it will typically remain suspended in the gel. These substances can include blood, pieces of connective tissue, or clumps of cells, which are collectively referred to as "floaters." Although 99% water, the vitreous does contain hyaluronic acid, hyalocytes that reprocess the hyaluronic acid, ascorbic acid, salts, sugars, vitrocin (a type of collagen), a network of collagen type II fibers, and a wide array of proteins in micronutrients. It also contains cells called "phagocytes" that remove waste cellular material over time.

A thin membrane of collagen called the vitreous membrane or hyaloid membrane encloses the vitreous. It is clear, transparent, gelatinous (2–4 times the viscosity of water), and thins with age. Relatively speaking, the few cells that it contains are mostly phagocytes, whose function is to remove debris. The hyaloid membrane, surrounding the vitreous, is attached only at the optic disc, where nerves pass from the photoreceptor system to the optic nerve, at the ora serrata, and on the top side of the lens, which is the junction of photo-sensitive and non-photosensitive areas of the retina. Vitrocin fibers floating within the vitreous are kept apart by electrical charges.

The most obvious purpose of the vitreous humor is to maintain a constant pressure, holding the shape of the eyeball in place.

Types of Vitreous Detachment

The pathology of PVD is always the same; however, its effects are different. There is no telling where the separation or tears will occur. It can occur:

- At the ora serrata (the junction of the retina and the ciliary body) and the vitreous humor straddles it,

- At the optic disc, where the membrane is attached to the retina,

- Or at a random place along the side of the hyaloid membrane (a thin transparent membrane enveloping the vitreous humor of the eye), leaving a space between the vitreous membrane and retina into which fluid can accumulate.

Symptoms

It is suggested that as much as up to 20% of PVDs are without symptoms. While they do not usually cause any permanent vision loss, they can be annoying, particularly related to an influx of vitreous floaters. Here are some symptoms to be on the lookout for:

- Sudden detachment of the vitreous from the retina area often causes flashes and/or floaters that look like lightning or electric sparks. Symptoms may last days to weeks.

- Sudden increase in the number of floaters

- Sudden ring of floaters to the temporal side of vision (toward the ears).

These symptoms may last days to weeks; however, it is critical to see your eye doctor immediately, at the first sign of any of these symptoms, to rule out the possibility of a retinal tear or detachment that is considered a medical emergency and a severe threat to vision. Your eye doctor will perform an immediate dilated retinal examination to determine whether you are dealing with a vitreous or retinal tear or detachment, or another condition altogether.

It is important to note that the risk of retinal detachment is greatest in the first six weeks following a vitreous detachment, but can occur over three months after the event. Between 8% and 26% of patients with acute PVD symptoms have a retinal tear at the time of the initial examination.

Causes and Risk Factors

- Aging - as the vitreous thins with age, the risk is greater

- People who are highly myopic (more than 6 diopters) are at greater risk of vitreous and retinal tears and detachments. Patients with myopia experience PVD approximately 10 years earlier than those who are farsighted (hyperopia).2

- Cataract surgery. This increases the risk for PVD. In one study, 75% of people with cataract surgery developed PVD. This includes cataract surgery by phacoemulsification, ultrasound to break up the lens that is then removed manually and replaced with an artificial lens.2

- Vitreous detachments can be caused by trauma or blows to the head, and even vigorous nose blowing.

- Excessive computer use may contribute to vitreous detachment as it restricts the free flow of blood and energy to the eyes.

- After menopause lower levels of estrogen may lead to changes in the vitreous. In premenopausal women, high levels of vitamin B6 may be connected to more frequent PVD due to their estrogen-dampening effect.1

- See "Drugs That Harm the Eyes" for a description of potentially harmful drugs.

- As a side-note, in lab animals it has been observed that the thinning vitreous makes the eye more vulnerable to cataract.3

Also see information about vitreous floaters.

Vitreous Detachment News

Want to learn more? See our blog for news on the vitreous.

See

Vitamins & Supplements to support the vitreous of the eye and overall eye health.

See

Vitamins & Supplements to support the vitreous of the eye and overall eye health.

Footnotes

1. J.Y. Chuo, et al, Risk factors for posterior vitreous detachment: a case-control study, American Journal of Opthalmology, December, 2006.

2. L. Gelia, Incidence, Progression, and Associated Risk Factors of Posterior Vitreous Detachment in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Sankara Nethralaya Diabetic Retinopathy Epidemiology and Molecular Genetic Study,

Seminars in Ophthalmology, August, 2015

3. Q. Li, et al, Oxidative responses induced by pharmacologic vitreolysis and/or long-term hyperoxia treatment in rat lenses, Current Eye Research, June, 2013

info@naturaleyecare.com

info@naturaleyecare.com

Home

Home

Vision

Vision Vision

Vision

Health

Health Health

Health Research/Services

Research/Services Pets

Pets About/Contact

About/Contact