Central Serous Choroidopathy (central serous retinopathy)

Vitamins/supplements Symptoms Causes Self help summary Self help discussion News

Central Serous Choroidopathy (CSC, CSR, or CSCR) (also referred to as "Central Serous Retinopathy") is most

often seen in young men, aged 20-50. Symptoms may include a fairly sudden onset of blurry vision

in one eye, dimmer colors, images seem in miniature or a blind spot in the center of vision.

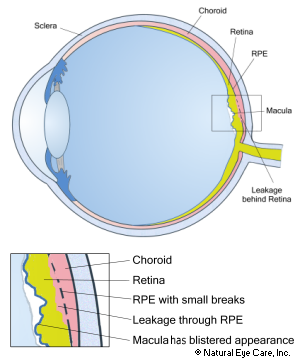

The disorder is characterized by fluid leaking from tissues behind the retina into mostly the

central macula area, resulting in detaching the macula from the tissue that supports it.

The leakage comes mostly from the choroid layer due to small breaks in the retinal pigment

layer (RPE). CSC/CSR patients typically have vision in the 20/20 to 20/100 range and a serous.

Sometimes a fluorescein angiogram is used to confirm the diagnosis.

Central Serous Choroidopathy (CSC, CSR, or CSCR) (also referred to as "Central Serous Retinopathy") is most

often seen in young men, aged 20-50. Symptoms may include a fairly sudden onset of blurry vision

in one eye, dimmer colors, images seem in miniature or a blind spot in the center of vision.

The disorder is characterized by fluid leaking from tissues behind the retina into mostly the

central macula area, resulting in detaching the macula from the tissue that supports it.

The leakage comes mostly from the choroid layer due to small breaks in the retinal pigment

layer (RPE). CSC/CSR patients typically have vision in the 20/20 to 20/100 range and a serous.

Sometimes a fluorescein angiogram is used to confirm the diagnosis.

Leakage due to CSCR comes mostly from the fine capillaries in the choroid layer, through, and because of, small breaks in the retinal pigment layer. Advances in technology have allowed re-searchers to identify poor multifocal choroidal hyperpermeability and hypofluorescent areas suggestive of focal choroidal vascular compromise. Some investigators believe that initial choroidal vascular compromise subsequently leads to secondary dysfunction of the overlying retinal pigment epithelium (RPE).

Researchers have linked macular thickness with CSCR, finding that these patients have low macular pigment optical density.5,6,7

Types of CSCR

Classic CSCR is caused by isolated leaks in the RPE that are visible via a technology known as fluorescein angiography. But ophthalmologists now understand that the condition can also take other forms.

Diffuse RPE dysfunction, known as diffuse retinal pigment epitheliopathy, occurs when the leakage and changes to the RPE are widespread.

Chronic CSCR is the term given to CSCR that endures for six months or more, compared to the normal duration of about 3 months.

Decompensated RPE is described as retinal detachment, combined with RPE atrophy and pigment mottling that continue to degenerate with time.

Symptoms

- A fairly sudden onset of blurry vision in one eye

- A blurry, dim blind spot in the vision center

- Objects appearing in miniature with the affected eye

- Distortion of straight lines, as similar to macular degeneration's distortions

Causes

The cause is unproven, but below are some likely contributors. Chief among these are high levels of stress, particularly in type “A” personalities (also often associated with hypertension), and ongoing use of steroids. One study also noted antibiotic use, alcohol use, untreated hypertension, and allergic respiratory disease as risk factors.8

- Stress. Most patients are young men (20-45) with aggressive "type A" personalities. Stress or trauma - both physical and emotional - appears to be an important risk factor. Researchers find that CSR patients have a higher stress scores.4

- Stimulants Use of drugs such as amphetamines, smoking, caffeine and other stimulants may be a cause.

- Anti-anxiety drugs. One study provides nationwide, population-based data on the incidence of idiopathic CSCR in adult Asians, and suggests that exposure to anti-anxiety drugs is an independent risk factor for idiopathic CSCR among males.

- Cortisol. The condition is also associated with high levels of the hormone cortisol, secreted by the adrenal cortex, that helps the body cope with stress. This is true of both morning and evening blood cortisol levels.4 High levels of cortisol characterize Cushing's syndrome, and research has found that 5% of Cushing's patients have CSR. Extensive research has indicated that corticosteroids, such as cortisone, which is prescribed for inflammation, skin conditions, allergies and sometimes eye problems can trigger CSC, make it worse, and/or cause relapses.

- Epinephrine used for various conditions such as asthma or obstructive sleep apnea.

- High blood pressure. CSR patients have diastolic and systolic blood pressure levels that are higher than normal.4

- Homocysteine. Researchers find that CSR patients have high homocystein blood levels.4

- Helicobacter pylori. There is evidence that this bacteria, naturally occurring bacteria in the body but prevalent in cases of gastritis, plays a role.

- Ischemia, an inadequate blood supply to an organ or part of the body, especially the heart muscles, or inflammation may contribute.

- Type II Kidney disease Patients with type II kidney disease (MPGN) can develop a variety of retina problems including CSR due to the same accumulated deposits that damaged the kidney membranes. Glomeruli are clusters of capillaries in the kidneys that help to filter waste from your blood. When these structures become inflamed because of the accumulation of “dense deposits,” a condition known as glomerulonephritis (GN) develops. These patients can similarly develop a variety of retina problems, including CSCR, due to the same type of accumulated deposits that damage the kidney membranes.

- Other drugs may include decongestants, erectile dysfunction drugs, and some anti-cancer agents. Chronic CSCR has developed from long-term testosterone treatment.

- Pregnancy. In women, pregnancy is a known risk factor.

Conventional Treatment

CSCR usually clears up by itself within 3–4 months. Patients who are using steroid drugs (for example, to treat autoimmune diseases) should discontinue using them, if medically feasible. However, any change in steroid drug use MUST be under the supervision of a physician.

Because of limited or poor study design, which interventions are most effective is debatable, but photodynamic therapy or micropulse laser treatment appears to be the most promising.

Photodynamic therapy. A photosensitizing drug is injected into the bloodstream and fills the abnormal, bleeding-blood vessels in the choroid. Then, a low-level laser light is applied to activate the drug, converting it into a substance that destroys the abnormal blood vessels without damaging surrounding tissue. In one large series of case studies, no patient developed severe visual loss or complications derived from PDT within an average follow-up of 12 months. However, nine cases developed reactive RPE hypertrophy after PDT. Possible side effects include temporary visual abnormalities, pain, swelling, bleeding, photosensitivity reactions (such as sunburn), inflammation at the site of the injection, joint pain, or muscle weakness.9

Laser treatment. Treatment with laser photocoagulation or hot laser that uses heat to seal or destroy abnormal, leaking blood vessels in the retina, may help patients with more severe leakage and visual loss, or longer persistence of the disease. The procedure is typically performed in the office, and a small number of patients will experience complications. The laser may permanently impair some central vision, due to the burning of parts of the retina, or reduced night vision, and a decreased ability to focus. The risks versus benefits are assessed on an individual basis, considering overall health, lifestyle, medications taken, etc. and must be discussed with your ophthalmologist. The risks need to be weighed against the dangers of allowing bleeding to continue or of trying other procedures.

Low-level heat laser therapy (transpupillary thermotherapy, or TTT). This treatment delivers less power for longer periods of time and is typically thought to be a lower risk alternative to hot laser. It introduces specific wavelengths of light through the pupil to the retinal pigmented epithelium and choroid tissues. It is thought to help accelerate the healing process while limiting the risk of damage to the retinal pigment epithelium. TTT may be helpful in CSR that lasts over three months, as it may help the RPE reabsorb subretinal fluid. Anti-vascular growth-factor injections have mixed results, but in theory, may help, such as through the upregulation of tight junctions between endothelial cells and the reduction of abnormal vascular channels.10

Methotrexate was shown to have potential as a treatment strategy.11 Finasteride is a safe and effective treatment for CSCR, and it may be a possible new option for the initial management of patients with CSCR.12

Complementary Treatment

The goal of the complementary approach is to nourish the retina, strengthen circulation and blood vessels, reduce inflammation naturally, and support overall eye health through targeted eye supplements, diet, and lifestyle modifications—all with the goal of preventing or reducing the risk of recurring CSCR. A range of nutrients has been well researched for helping improve circulation to the retina, improving retinal thickness, reducing inflammation, strengthening related blood vessels, and eliminating waste. Researchers have demonstrated that the following nutrients support retinal health and help improve retinal thickness.

In a small study researchers found that treatment of CSR patients with melatonin benefited both vision acuity and the density of the macular pigment.1

Certain nutrients such as zeaxanthin, lutein, astaxanthin, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamins C and D3, resveratrol, grapeseed extract, and meriva may help support remaining vision for those suffering from central serous choroidopathy.

Researchers found that although blood levels of lutein improved in CSR patients treated with 20mg daily, macular pigment density did not - however, the condition remained stable while in the control patients given placebo, macular pigment density continued to thin.2 Another study treating CSR patients with high dose antioxidants found similar results, little improvement, but no worsening of the condition.3

Check creams and nasal sprays for corticosteroid ingredients, and if possible, reduce or eliminate their use with your medical practitioner's supervision.

Daily juicing of vegetables and fruits (preferably organic). Our recipe for this condition is some combination of the following: ginger, garlic, leeks, parsley, beets, cabbage, carrots, celery, spinach, kale, collard greens, apples, grapes, raspberries, lemon, chlorophyll, wheat grasses - (not too much fruit). See more info on juicing.

Our vision wellness recommendations. See these essential vision tips as the foundation for your good vision.

Related Conditions

- Macular degeneration

- Diabetic retinopathy

- Posterior vitreous detachment

- Hypertensive retinopathy - high blood pressure can cause damage to the retina

- Cushing's syndrome - high levels of cortisol in the blood (can be due to prolonged cortisoid medication use) which affects the adrenal gland. It can give rise to high intraocular pressure, protrusion of the eyeball, or to steroid induced cataracts.

CSR News

Want to learn more? See our blog news on CSR.

Find Vitamins & Supplements to Support the Retina

Find Vitamins & Supplements to Support the Retina

Footnotes and Research

Although the underlying physiological cause may be unique, there may be similarities in terms of nutritional, diet and lifestyle recommendations made by Dr. Grossman for eye conditions (such as macular degeneration) that result in similar vision symptoms.

1. A. J. Gramajo, G. E. Marquez, et al. (2015). Therapeutic benefit of melatonin in refractory central serous chorioretinopathy. Eye, August, 2015.

2. M. Sawa, F. Gomi, et al. (2014). Effects of a lutein supplement on the plasma lutein concentration and macular pigment in patients with central serous chorioretinopathy. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, July, 2014.

3. M. Ratanasukon, et al. (2012). High-dose antioxidants for central serous chorioretinopathy; the randomized placebo-controlled study. BMC Ophthalmology, July, 2012.

4. A. Agarwal, G. Garg, et al. (2016). Evaluation and correlation of stress scores with blood pressure, endogenous cortisol levels, and homocysteine levels in patients with central serous chorioretinopathy and comparison with age-matched controls. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology, November, 2016.

5. Dinc, U.A., Yenerel, M., Tatlpinar, S., Gorgun, E., Alimgil, L. (2010). Correlation of retinal sensitivity and retinal thickness in central serous chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmologica, 224(1):2-9

6. Sasamoto, Y., Gomi, F., Sawa, M., Tsujikawa, M., Hamasaki, T. (2010). Macular pigment optical density in central serous chorioretinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, Oct;51(10):5219-25.

7. Putnam, C.M., Kinerk, W.T., Bassi, C.J. (2013). Central serous chorioretinopathy produces macular pigment profile changes. Optom Vis Sci, Jul;90(7):e206-12.

8. Haimovici, R., Koh, S., Gagnon, D.R., Lehrfeld, T., Willik, S. (2004). Risk factors for central serous chorioretinopathy: a case-control study. Ophthalmology, Feb;111(2):244-9.

9. Ruiz-Moreno, J.M., Lugo, F.L., Armadá, F. (2010). Photodynamic therapy for chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Acta Ophthalmol, 88(3):371–376

10. Mathur, V., Parihar, J.K.S., Maggon, R., Mishra, S.K. (2009). Role of Transpupillary Thermotherapy in Central Serous Chorio-Retinopathy. Med J Armed Forces India, Oct; 65(4): 323–327.

11. Kurup, S.K., Oliver, A., Emanuelli, A., Hau, V., Callanan, D. (2012). Low-dose methotrexate for the treatment of chronic central serous chorioretinopathy: a retrospective analysis. Retina, 32(10):2096–2101.

12. Moisseiev, E., Holmes, A.J., Moshiri, A., Morse, L.S. (2016). Finasteride is effective for the treatment of central serous chorioretinopathy. Eye (Lond), Jun; 30(6): 850–856.

info@naturaleyecare.com

info@naturaleyecare.com

Home

Home

Vision

Vision Vision

Vision

Health

Health Health

Health Research/Services

Research/Services Pets

Pets About/Contact

About/Contact